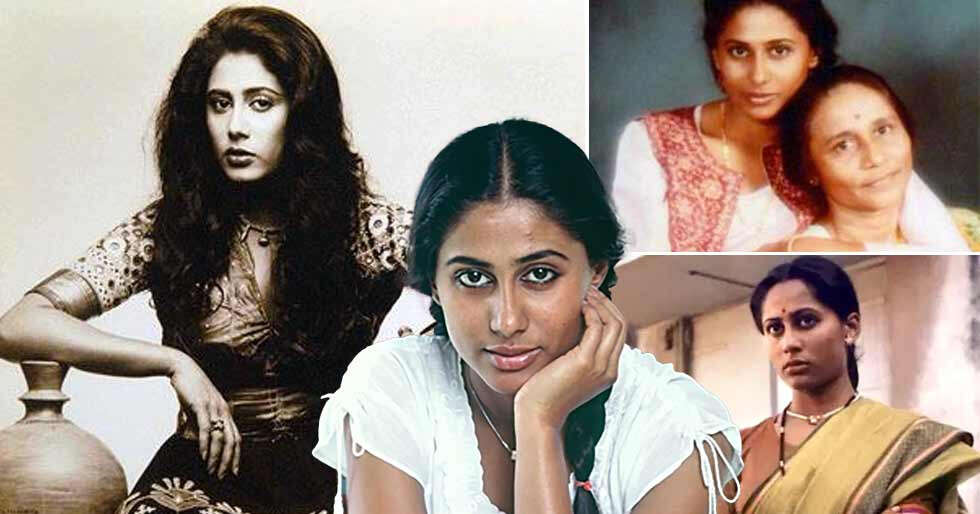

EXCLUSIVE: “Smita was a victim, not a villain,” says Manya Patil-Seth

EXCLUSIVE: “Smita was a victim, not a villain,” says Manya Patil-Seth

That her memories are inextinguishable is evident in sister Manya-Patil Seth’s post on Instagram which reads, “Those who are never forgotten don’t need to be remembered.” The pain is as plain when she says, “A part of Smita’s life was so glorious… yet another so excruciating. A decision that destroyed her…”

Manya Patil-Seth responds to our questions in a heart-to-heart conversation… Excerpts:

SOUL TWINS

Smi (Smita) was the middle born amongst us three sisters. Anita (Patil-Deshmukh, a neonatologist) is the eldest and I’m the youngest. We grew up in rustic Pune. Smi was an absolute tomboy – playing outdoors with the kids in the neighbourhood … gilli danda (tipcat), dabba eyes spies (hide-n-seek). She was sporty, jumping from trees, beating the boys in the games… an absolute terror! In school, she participated in sprinting races and javelin throw at the state level. I was the shy one. I’d observe her from a distance. I didn’t like to dirty myself.

Being closer to Smi in age, I bonded with her. Smi and I shared a room for many years. Though our features are different, I’m told there’s a jhalak of her in me. Maybe it’s the expressions in the eyes, the vibe… In fact, Mahesh Bhatt once remarked, “You two sisters are so alike. One begins a sentence, the other finishes it. Even your reactions are similar. I should make a film titled Sisters with you.”

OFFBEAT PATH

My parents (father Shivajirao Girdhar Patil was a Minister in the Maharashtra cabinet and mother Vidyatai Patil was a social worker) were socialists. The atmosphere at home was progressive. We were given the option to choose our careers. The only rider was to be the best. When Smi began reading the Marathi news (Batmya) on Doordarshan in the early ’70s, her face mesmerized viewers. People began watching the news because of her. Those days, electronic shops had televisions relaying shows continuously. When Batmya began, people would stop outside the showroom to watch her. Maa (mother Vidyatai) rightly described her face as ‘mohak’ (alluring). It was difficult to look away from her.

Smi’s film career took off after Shyam Benegal cast her in Charandas Chor (1975). She went on to feature in several films including his Nishant, Manthan, Bhumika, Mandi… Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh and Ardh Satya, Rabindra Dharmaraj’s Chakra (between 1975-1983)… Art films required her to be natural. So, she wore no make-up except kajal. Her complexion was sawla (dusky), something which was a point of contention those days. But Maa loved it. She said it was like Lord Krishna’s. However, Smi didn’t have great skin. Being a premature child, she suffered from gut issues. She was also a high-stress person. She’d often burst out into pimples. Yet, she wouldn’t use foundation to camouflage them.

COMMERCIAL FORAY

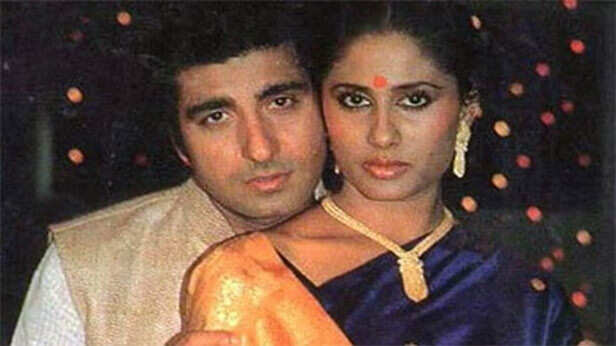

When she began shooting for Ramesh Sippy’s Shakti (1982), her initial commercial outing, he persuaded her to wear make-up. He explained she’d look odd on screen as everyone else would be with make-up. Eventually, Smi relented. There was a scene in Shakti where she had to tell Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay, ‘Main tumhare bachche ki maa banne wali hoon.’ A visibly upset Smi came to the dressing room and said, ‘I can’t say this idiotic ghisi peeti (clichéd) line!’ Finally, after much discussion she agreed to say, ‘Main maa banne wali hoon.’ Usually, with seasoned filmmakers/actors an actor tends to get intimidated. But she didn’t.

Smita did commercial cinema (including Namak Halaal, Aakhir Kyon?, Nazrana, Amrit in the ’80s) only to prove a point. “I want to draw audiences to the smaller socially relevant films. The commercial actor’s reach is wider,” she’d say. Many a time, she was made to believe she’d be working with a certain filmmaker. But when it didn’t happen, it would disturb her. She’d say, ‘I can’t sweet talk to people.’ It’s no secret that as a result she lost many roles.

BEST BHUMIKA

Smi’s oeuvre was immense but Shyam Benegal’s Bhumika (the 1977 film was based on Marathi actress Hansa Wadkar’s unconventional life) is my favouritest. I see so much of Smi in the protagonist Usha. The graph that Usha goes through, the shades through different stages of her life… mirrored my sister. Smi was a rebel and yet wanted to fit in. She wanted the traditional life and yet felt claustrophobic with it. The complexities and contradictions in her personality, the tendency to give her all in love… All this helped Smi make a success of that character. She understood the character instinctively, more than intellectually – she was too young being in her early 20’s then.

Interestingly, Smi’s Sulabha Mahajan in Jabbar Patel’s Subah (Umbartha in Marathi, 1982) was inspired by my mother, a social worker. Smi’s gait, her body language… was all based on Maa. In fact, she wore my mother’s sarees and pinned them up in pleats just the way Maa did. She wore the watch with the dial on the inner wrist like Maa. The film’s subject invited huge controversy. Sulabha’s family is also engaged in social work but keeping in mind the conveniences of life. They can’t understand how a woman’s love for her work could take precedence over her child. But Sulabha sees through their hypocrisy.

UNIQUE FACETS

Her stardom aside, at home Smi had no qualms doing jhadoo katka if the need arose. She liked arranging her own things. She collected a lot of folksy artifacts – masks, puppets, embroidered and earthy fabrics – during her rural visits. She treasured silver showpieces. Above all she loved mogras. That love came from our childhood in Pune, where gardens full of mogras, jui and jai flowers surrounded us. She had an exquisite collection of cotton sarees. I’ve kept a few as souvenir. But what she loved most was wearing jeans with Kolhapuri chappals, oxidised silver bangles and tying her hair in a knot.

Smi was an adventurist. On impulse she’d get into her car/bike and go off. Once she went off to meet Govind Nihalani, whom she fondly called Govinda, in Delhi. He was doing the cinematography for Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982). Her two friends and she drove back in an open Jonga jeep through the Chambal Valley in times when dacoits were a real threat. She was that free-spirited. Bold and bindaas.

Her quest for photography was fascinating. With the Nikon F 2, she captured candid images of her co-artistes on sets. She even learnt to develop and print the black and white negatives in the labs of her photographer friends. The lens through which she saw the world was unique, humorous, empathetic and often surprising. ‘Through The Eyes of Smita’ is a curated exhibition of photographs shot by her.

Stories of her compassion and empathy abound. At my sangeet ceremony, the first thing she did was to meet and greet the singers and musicians. She served them food saying, ‘Aap pehle khayenge!’ She believed they deserved that respect. She helped out friends with money though most never returned it.

Undeniably, Smi was temperamental and volatile. She was extremely sensitive and sometimes unnecessarily so. She was both loving and possessive. She would demand attention and give it as well. She couldn’t tolerate emotional dishonesty. There was an element of self-destructiveness too.

MARRIAGE OR MIRAGE

When she got involved with a married man, Maa was terribly upset. My parents called Raj (Babbar) home. They told him you’re a married man, you’re committed and that you must find an appropriate solution. Maa was so upset with Smi that she stopped talking to her for a long time. She said, ‘You’re turning into a home-breaker.’

Yes, Smita did feel guilty about the situation. Smi’s relationship was a red flag at the onset. It was never smooth. It had its ups and downs. It soon turned toxic. I remember telling her, ‘You’re so troubled, so emotionally on-the-edge all the time.’ She said, “I have to allow this tragedy in my life to feel these emotions. I can’t and don’t want to protect myself from them. It’s from here that I’ll draw as an actor.”

Above all, she loved children, she yearned for one. Maa said you can find yourself an excellent partner if you give yourself a chance, instead of being in a relationship, which had no future. Smi didn’t agree. The initial euphoria aside, it was a not-so-happy pregnancy because the relationship turned out to be different from what she’d expected. The situation had turned ugly. She was not the villain, rather a victim. She was being exploited personally and financially. She was systematically distanced from those close to her, even her childhood friends.

TRAGIC TURN

Yes, Smi had a premonition of dying young. She’d say, ‘I won’t live beyond 35.’ I’ve preserved a book in which she’s written something to the same effect. Those days I was based in New York. But I kept visiting India for some formalities. At times I stayed with her. That’s when I saw a lot of disturbing things. Her close friends, even industry people, knew what was going on in her life.

Smi had also started feeling ashamed of herself. She couldn’t reconcile with this Smita. One side of her was independent, a trailblazer, an actor who played inspiring roles. The other side of the coin was a fearful woman, emotionally manipulated and controlled by someone and going through humiliation. The dichotomy in her personal life was terrible. She was a wreck. She had told her friends, ‘I’m going to get out of it. I must do it for my child. I have a reason to correct myself.’

When she fell ill due to post-partum complications and was taken to the hospital, Anita was in Chicago and I was in New York. Both of us were to fly to India together. Later in the night, Papa called me to say Smi had passed away (reportedly due to puerperal sepsis on 13 December 1986). I was numb. I had to break the news to Anita at the airport, who had flown from Chicago to join me. Anita walked towards me spreading her hands to hold me. I said, ‘Papa said she’s no more.’ That was the worst moment of my life. I cannot forget the expression in Anita’s eyes.

Back home at the cremation there were crowds, crowds and crowds… Smi was dressed as a bride and her make-up was done by Deepak Sawantji, someone who’d been with her and seen it all. I couldn’t cry at all. Years later, I’d arranged a special screening of Bhumika. After returning home, I shut myself in the room and cried for hours. In Usha’s character I saw my sister – a rebel, craving for normalcy in her life and authenticity in her relationships.

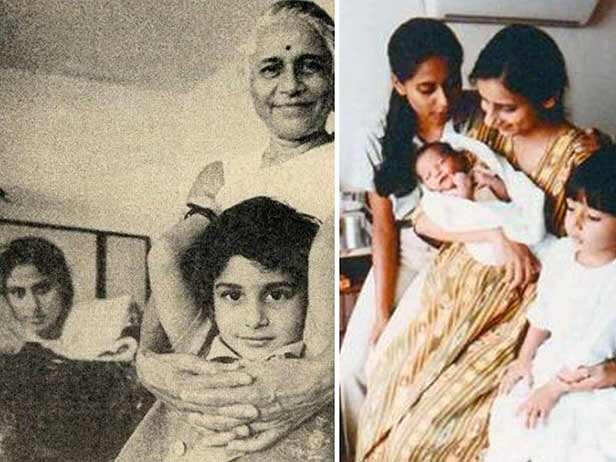

MAA & PRATEIK

Maa had witnessed Smi’s pain first hand through the last part of her life. How difficult it must have been for a person, who was so strong, so vociferous to watch her child suffer. But she wiped her tears to look after someone who was as unhappy as her. I’d tell Maa that Prateik needs to be sent away to New York, away from constant references to his mother. Everywhere he went he was ‘bechara’ Prateik or Smita Patil’s ‘motherless child’. It was messing with his mind. On the other hand, he was over compensated. It was not a healthy scenario for him to grow in.

Prateik has lived with his share of trauma. Till date, he cannot watch his mother’s films. To him she’s an illusion, an all-encompassing chimera. All his life he’s lived under this overarching collective recollection, things he keeps hearing about her… without any real connection with her. It’s bizarre.

Prateik and I share a close equation, an instinctive bond. He doesn’t have to explain a thing to me. I understand it. More than our own children, we sisters love Prateik. He knows that and so do our children. He’s the person we protect. He has no dearth of love. Yet no one can make up for his loss. How he forms a relationship with his father is not for me to interfere or judge.

A tragedy like this changes you forever. Death doesn’t disturb me now. Because no matter what you do, what remains is that picture in the frame and some memories. What makes me cry is the sadness of the people left behind. Though I’ve been approached to do so, I cannot bring myself to write Smi’s biography, which would require sharing many details of her life . She had placed her trust in me as a confidant. Some of the truths are only for me to know.