Review – Joan Baez: I Am a Noise

Review – Joan Baez: I Am a Noise

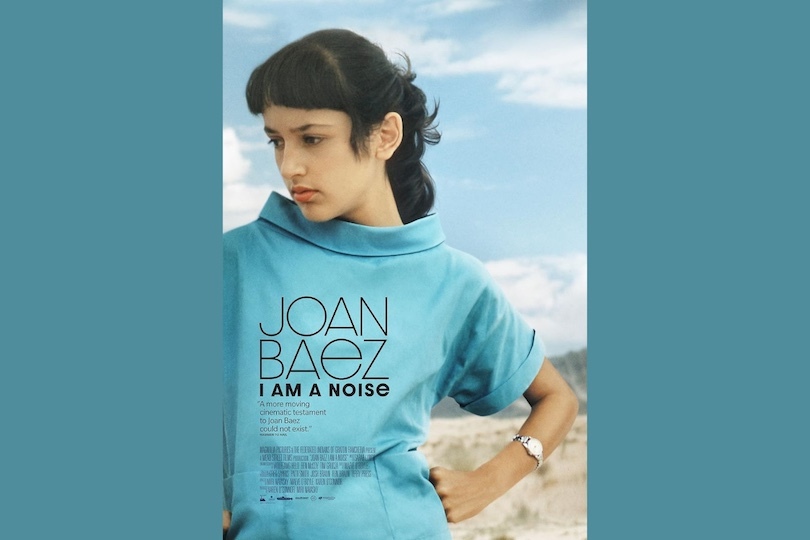

Joan Baez: I Am a Noise

Directed by Miri Navasky, Maeve O’Boyle and Karen O’Connor

Magnolia Pictures International, 2023

Students of international relations will welcome this timely 2023 movie-portrayal of the legendary protest-singer, Joan Baez. Its streaming imagery depicts a stardom engaged as much in social justice as in the music industry. Directed by Miri Navasky, Maeve O’Boyle and Karen O’Connor, the Magnolia Pictures film bulges with historical material and international happenstance. Rocketing into public life as a teenager, (and through grainy photomontage curated by Magnolia) we see how Joan marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr, and co-performed (with her then-boyfriend) Bob Dylan – happily in the right place and time, and always making headline-news.

Whether portraying Baez’s Civil Rights or anti-Vietnam crusading, or (more recently) LGBT, environmental and pro-Catalan activism, this unconventional biopic offers much to interest the IR reader. Magnolia Pictures released this auricular feature-documentary, partially curating from filmography archived during her 2018 farewell tour. It is now also accessible on the Internet Movie Database (IMDB.) The young Joan is voiced by Hanna Shykind. The cast is impressively five-star- featuring (extensively) not just the singer but also both Clintons; Richard and Mimi Farina, Bob Dylan, and Michael Moore. Much of the total 115m footage has never been seen outside media circles. Accompanying cinematography is beautifully executed by Timothy Grucza, Wolfgang Held and Ben McCoy. Incidental music was composed by Sarah Lynch.

“I Am a Noise” tenderly exposes the personal angst underlying Baez’s public persona. Towards the start, Joan confides, ‘I am far better at dealing with 2,000 people in a theatre…than with one person in a room.” Beautifully presented cameos lay bare the star’s idiosyncratic personal foibles and “self-confidence traumas”. Behold in one movie, sixty jam-packed years of musical and political expression. IR specialists will be most interested in the frank portrayal of her overt social consciousness. When the legendary singer says, ‘I was never interested in the cameras- in fact I hated them and saw them only as a necessary evil to focus… on a cause’, this is aptly documented by Magnolia in the many occasions she shuns reporters or breaks cameras, to advance campaigns or protect innocent victims.

As this movie shows, in 1956, Baez was moved by the speechmaking of Martin Luther King Jr. We see them become friends. The film addresses the FBI smear campaign alleging she was personally intimate with King. One of its strengths is that the movie is deliberately ambiguous on this detail. However, it is more direct in showing her rendition of “We Shall Overcome” (the civil rights anthem written by Pete Seeger and Guy Carawan, at the 1963 March on Washington) propelling the young singer to cult status in the burgeoning American protest movement. This is probably the film’s biggest moment.

Baez masterfully unites song and message. Repeated again during the mid-1960s Free Speech demos at UC Berkeley, and at many other rallies, Magnolia thus shows how her dual-career sky-rocketed. For example, her recording of the song “Birmingham Sunday” (1964), written by her brother-in-law, Richard Fariña, appears in 4 Little Girls (1997), Spike Lee’s expose of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. The movie then depicts her launching nonviolent protest and fronting the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches. Jail-time for Vietnam-activism followed. As she put it in the movie, ‘I went to jail… for disturbing the peace; I was trying to disturb the war…

Already highly visible in civil-rights, Magnolia delineates how Baez vocalized her opposition to the Vietnam War by creating the Institute for Nonviolence and vehemently advocating draft resistance at her concerts. In 1966, Baez’s autobiography, Daybreak, was released. It outlined her anti-war position and dedication to victims imprisoned for resisting the draft. Magnolia brings her book, and these prescient events to life, including how Baez was arrested and jailed twice in 1967 for blocking the Armed Forces Induction Center in Oakland, California.

One of the recurrent images of “I Am a Noise” are anti-war marches. For instance, we see her in Christmas 1972, in a peace delegation to North Vietnam, and caught in the U.S. military’s “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi. In 2016, Baez advocates for the Innocence Project to exonerate the wrongfully convicted. Magnolia release unseen (if frustratingly grainy) images from December 2005, as Baez sings “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” at a demo outside the San Quentin State Prison. This sit-in opposed the execution of Tookie Williams. She had previously protested for Robert Alton Harris.

Magnolia brings these salient events to life, sometimes superimposing fresh imagery on 1960s photo-reels. Some of the earlier filmography is patchy in quality. As we get closer to the present the visual and audio synthetization improves so that we have a sense of viewing two movies in one. The film also explores her promotion of LGBT rights including concerts against the Briggs Initiative, which proposed banning openly gay people from teaching in public schools in California. We see her participate in memorial marches for the assassinated San Francisco city supervisor, Harvey Milk and writing “Altar Boy and the Thief” (Blowin’ Away, 1977) as a dedication to her gay fanbase. Sound-distorted clips of the past are deftly interspersed with modern portrait cinematography. This is temporally atmospheric, yielding a sense of time passing.

Film scenes show Baez in 2009 re-casting “We Shall Overcome” cunningly infused with Persian lyrics in support of peaceful protests by Iranian people. We witness her dedicate the song “Joe Hill” to the people of Iran during her concert at Merrill Auditorium in Portland, Maine in July, 2009. Around the same time, she become active in defence of ancient redwoods such as the Headwaters Forest. There are some superb geographic still-shots of Yosemite and Tuolumne County. Again, faded monochrome juxtaposes with technicolour.

The camera tripod switches erratically from archive to contemporary- which may challenge inexperienced viewers. However, by doing so, Magnolia offers us a wide-angled view of Baez from the 1960s to (then) addressing rallies in San Francisco protesting the U.S. invasion of Iraq; to Emmylou Harris and Steve Earle in London, at the Concert for a Landmine-Free World. There are clips of In the summer of 2004, when Baez joins Michael Moore’s “Slacker uprising Tour” of American college campuses, backing peace candidates in the presidential election.

While she shuns mainstream politics, Magnolia depict Baez’s San Francisco Chronicle landmark endorsement of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential election: “Through all those years, I chose not to engage in party politics. … At this time, however, changing that posture feels like the responsible thing to do. If anyone can navigate the contaminated waters of Washington, lift up the poor, and appeal to the rich to share their wealth, it is…Obama.” Playing at the Glastonbury Festival, Baez states Barack ‘reminds her’ of Martin Luther King Jr. The movie also portrays her political scepticism: “In some ways I’m disappointed, but in some ways, it was silly to expect more… Once he got in the Oval Office, he couldn’t do anything.”

The film shows her famous White House performance on February 10, 2010, celebrating the civil rights movement, and her 2011 ‘Occupy-Wall-Street’ appearance. We see how on July 21, 2019, she defends jailed Catalan independence leaders as ‘political prisoners, and visits incarcerated former President of the Parliament of Catalonia, Carme Forcadell. Magnolia also covers the March 18, 2011 launch of Amnesty International‘s Joan Baez Award.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez observed — “Everyone has three lives…public, private, and secret.” We see the public and private Baez in abundance, and she now reveals secrets surrounding her anxiety and child abuse. There are extensive personal revelations about stage-fright in concert and campaigning. As Bob Hahn shows, “By pulling the curtain back from this part of her life and the challenge of confirming who was the abuser, Joan offers a message to the hundreds of folks who struggle with similar invisible injuries”.

This movie is strongest on personal scale. Baez talks on camera about how time ‘withered her voice’, but deft camerawork shows her years have compensated by generating wisdom to make the songs resonate internationally. In contrast, archivally this coverage is (understandably) weaker. She describes repressed memories of being abused by her father as “the bone-shattering task of remembering.” As with the FBI material, the film suffers an inherent research deficit- stories elusively locked away, which may not be known until a future date.

Elsewhere: gold mines of visual material: journal etchings, concert footage, family videos and vintage photographs. Included in the mix is audio from her therapy tapes, setting the stage for her unflinching confessional about abuse. As Baez emotionally excavates these items from her mother’s storage unit, memories come alive, as if we are with her on this journey. She calls these. “The kernel” of her interior darkness.

At the end, as we see Joan at peace with her son Gabriel Harris, accompanying her touring band for the farewell gigs, Baez exhibits equanimity in the face of enormous loss. From monochrome to technicolour, we see how she positively moved the world. Baez never wanted the film to be a hagiography but an honest portrayal, “down to warts and wrinkles.” In the film epilogue she confesses that only the sad passing of her parents and sister ‘made it possible to talk.’ This is a performer who genuinely ‘made music count’. IR students will find so much of interest in this frank filmographic confessional of a life simultaneously spent in international music and protest.

Further Reading on E-International Relations