US-China Hegemonic Rivalry in Africa

US-China Hegemonic Rivalry in Africa

[ad_1]

This article is part of the US-China Dynamics series, edited by Muqtedar Khan, Jiwon Nam and Amara Galileo.

Africa is still affected by hunger and malnutrition, despite its description as the food basket of the global system. This recurrent problem is partly due to the outbreak of COVID-19, climate change (inaction on climate change by African governments), conflicts in some African states, and an unhealthy rivalry between China and America who together largely dominate imported food supplies. By this, Africa is vulnerable to all manners of burdens inherent in the terms of reference embedded in most of the agreements and partnerships from these global giants. Importantly, while China and America compete sternly to partner with Africa as proposed by SDG 17, in a bid to achieve other goals, especially “food for all or no hunger”, evidence shows that this gesture is more of competition for power and influence over Africa’s food security sector. Consequently, this leads to the impoverishment of Africa, especially, in food security and by extension, food sovereignty. It has made Africa lose ownership of some of its resources such as medicinal plants (hoodia from San), arable lands and water along coastal lines to China or America all in the name of partnership (Amusan 2017). This is concretised through controversial intellectual property rights (IPRs) (Bond, 2006). Comparatively, Africa contributes the least to the emission of greenhouse gases but suffers the most from and since Africa is largely dependent on agriculture, which is climate-sensitive (Nyasimi et al 2013), its ability to produce food to eradicate hunger and malnutrition is steadily hampered.

Although the global system has proposed SDG 13 (Action on Climate), to combat climate change in a bid to promote food security, African governments seem to be lacking the required technologies, governance, and resources to adequately and urgently take action through climate adaptation and mitigation. This has further pushed Africa to depend on a partnership with countries like China and America; indeed, the two states have extended assistance to Africa in the area of climate change. In 2021, China and Africa collaboratively made a declaration to combat climate change in the continent. Beijing specifically launched over 100 clean energy and green development projects to assist African countries in better utilizing solar, hydropower, wind, biogas and other renewable sources of energy (Forum on China-African Cooperation 2021). China has been committed to investing in Africa, especially on environmental issues, since the late 1990s (Li et al 2013). This investment is made possible because of China’s economic development, though this is not without some challenges due to the contribution of this development to environmental hazards (Economy 2007; Kaplinsky & Messner 2008).

China’s political and economic status, especially in Africa, has continually challenged the US. This, over the years, has constituted a rivalry over which country holds the greatest influence on the global system (Economy 2018; Sutter 2016). Relatedly, through the initiative of the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (NAFSN), the US aimed to transform 50 million Africans from poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2022 (USAID 2021). America had supported Africa to combat the impacts of climate change, especially in areas of mitigation and adaptation. It offered technical support to incorporate Climate-Smart-Agriculture (CSA) into national and regional food security plans and uses climate data, modelling and training to assist African countries in adopting CSA (USAID 2021). Similarly, America had been committed to offering technical support to strengthen the African Union (AU) Commission to empower women in agriculture (AU 2022). America has also been contributing to poverty alleviation in Africa through NAFSN, which increases private sector investment and public-private partnerships for smallholder farming (USAID 2021).

All of these imply that China and America have played a critical role in food security in Africa. However, a tangible proportion of Africa’s population still suffers from hunger and malnutrition. These circumstances have partly been blamed on rivalry in Africa’s food security sector and the ulterior motive behind most assistance and partnerships from these global economic giants. Thus, when one contextualizes the politics behind food aid in developing areas as discussed by many scholars (Ravenhill 2017; Thomas, Lamy & Masker 2019; Webb & Thorne-Lyman 2007), gestures may be seen as Greek gifts in the long run.

China’s relations with some African countries over loans, financial assistance, and seizures of national assets show that Beijing’s partnerships with Africa are largely motivated by investment and profits. Despite China’s presence, in terms of assistance and collaborative action on climate change with some African governments, the import of food supplies continues at about 85%, making an annual food bill of $35 billion (Olander 2021). Over-reliance on imported food leaves most African countries vulnerable to China and America’s hegemonic rivalry in food security. This vulnerability, before now, has been typically blamed on civil wars (e.g. Liberia and Sierra Leone) and inter-state wars (e.g. Ethiopia-Eritrea). Similarly, climate change is a serious threat to food production in Africa. Greenhouse gases increase tendencies of famine and drought in some African states (Amusan and Olutola 2016).

Exacerbating the situation, the World Food Program (WFP) reports that hunger has increased by 30% since the outbreak of COVID-19, which is the highest level in a decade (WFP 2021). The questions then are, what could have happened to various data and statistics that predicted Africa as the food basket of the world? Could it be that partnerships and supports from China and America are means of consolidating their hegemonic influence and power on Africa’s food security sector? What is the motive behind their hegemonic rivalry in Africa’s food security? Could cooperation rather than the rivalry between these global giants be beneficial to food security in Africa? These questions bring to the fore the relevance of this article, which seeks to examine the hegemonic rivalry in food security between America and China in Africa. It specifically advances knowledge about the remote rationale behind China and America’s dominance by design in the food security of Africa. Research in this field will enhance understanding of how cooperation rather than conflict between China and America could assist Africa in achieving SDGs 1, 2. 14, and 15 by 2030.

Problematizing China’s and America’s Hegemonic Rivalry

Africa, like other continents, has a target of meeting all the 17 SDGs, globally set to be accomplished by 2030 (UN 2015). One of these goals is “no hunger or food for all”. By this goal, it means that countries must be food secure in terms of food availability, accessibility, affordability, stability, and utilization (UN 2015). However, the combination of factors such as negative impacts of climate change, explosive population, conflicts, poor governance, increased inequalities, and poverty among others have made Africa suffer from hunger and malnutrition (Amusan 2010). Hence, its reliance on food assistance from developed countries. Farmers in Africa, especially women, lack information on climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, which not only contributes to gender inequality in the agricultural sector, or a threat to food production and distribution, but also aggravates poverty situations in the continent (Amusan 2014; Agunyai & Amusan 2023). Conflicts, poor governance, and rapid population growth are partly agents of food insecurity in Africa. Farmers who are displaced from working on their farms, due to conflicts and natural disasters, would contribute very little or nothing to food production and distribution. These circumstances have continually rendered Africa vulnerable to inordinate and unhealthy rivalry practices. This often takes the form of scrambling for food assistance through humanitarian assistance partnerships as dictated by SDG 17 from China and America.

Despite measures to address Africa’s vulnerability through supposedly assistance and partnership programs from external powers, Africa has continually struggled with the problem of food insecurity (Carmodi 2011; Paarlberg 2013; Agunyai 2023). According to the 2022 Action Against Hunger release, hunger and malnutrition have remained entrenched. China and America have been supporting Africa in critical areas of food security, especially on climate change, adoption of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) with emphasis on food and animals, transfer of agricultural technologies, and provision of credit and financial assistance – yet, as noted, positive outcomes remain elusive which questions the motives of both China and America (Ferchen, 2022). Based on the results, it seems that the rivalry for dominance and influence between China and America (under the guise of assisting Africa to achieve food security) has further impoverished the continent. One way to see this is through large scale farming being introduced to the continent – which focuses more on the production of industrial inputs, alternatives to fossil fuels, animal feeds and possible exportation of produced food to the home states of producers (Lymbery and Oakshott 2014; Pearce 2012). Their activities impair the supposed advantages of foreign direct investment (FDI) and corporate social responsibilities that are claimed to be an engine of growth and development in developing areas (Amusan 2015). China and America’s hegemonic rivalry looks like the recolonization and impoverishment of Africa to further industrialize their own country (Olander 2022, Ferchen 2022). A further example of this can be seen with the introduction of “terminator seeds” (Amusan 2019; Walters 2011) and GMOs (Howard, 2016).

This article is premised on the fact that, if the current hegemonic rivalry persists, Africa’s target to achieve SDGs 1, 2, 14, and 15 may remain a mirage. Extant studies on China’s and America’s collaborations with Africa have been too focused on rivalry, while a potential cooperation for Africa’s food security goal is rarely examined (The Conversation 2020). This constitutes the major concern of this article, using cooperation between China and America as the basis for the achievement of sustainable food security in Africa from an agroecological perspective.

Mapping the Application of Agroecological Theory

Agroecology holds the view that new standards or models of management remain the basis for carrying out ecologically biodiverse, sustainable, resilient and socially just agrosystems (Altieri 1995). It specifically stipulates that the combination of science with traditional, practical, and indigenous knowledge will adequately boost sustainable agricultural production systems. It sees local communities and farmers as agents of change. The theory advocates for the autonomy and adaptive capacity of local producers in a bid to bring the needed development in systems of the food chain. It is also premised on the idea of furnishing local producers, communities, and farmers with adequate information, a guide of action, techniques, innovations, and ideas that are rooted in societal features such as collective action and quality of coordination that collaborate the organic management of natural resources. Relatedly, the theory gives credence to societal aspirations that frown at, contest, or question the intensification and standardization of production and consumption systems (Gliessman 2015).

The theory has some variables in common with social constructivism. It pushes for commitment to ethical values, and responsible development for a sustainable futures with a goal to enhance sustainable systems of food production that are rooted in the aspirations of the people who abided with their ethical values. It argues that for food security to be adequately sustained, scientific knowledge should be combined with traditional knowledge held by those in a position to take action. This theory warns that all actions on food sustainability systems should not only be given to scientists or experts but, also, opportunities should be given to new categories of stakeholders in the decision-making process. The participation of new actors is premised on two factors. First, it is generally known that the evolution of public policies enhances collective procedures of decision-making. New actors are thus involved in planning processes that engage their shared roles. Second, in the context of growth, allowing the sphere of new actors is encouraged with the transgenic revolution. These socio-technical controversies shape the basis of a “dialogic democracy” that contributes to the redefinition of the social pact between scientists and the indigenous knowledge system. Callon et al. (2001) argue that agroecology provides room for innovative collective actions and “hybrid forums” to promote sustainable socially inclined development be it in food production, democratic settings, or the environment. Limiting the role of science or experts, complexity and uncertainty of living systems creates space for new decisional roles that are occupied by epistemic communities.

It is argued that such collaborations that respect ethical and societal aspirations are best set up for adaptive governance on territories. It goes to show that countries extending partnerships or collaborations to other countries should offer such assistance with the genuine reason to share their scientific knowledge with local stakeholders. This ought to go with adequate respect for recipients’ ethical values. It should be done to promote the aspirations of the states that need assistance, with little or no emphasis on the imposition of their standardized systems of production and consumption on the beneficiary states. The theory argues that sustainable development in food security and other related concerns largely depends on the autonomy and adaptive capacity of the concerned states. Agroecology offers an action based foundation that rebuilds ecosystems and delivers safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, culturally appropriate, and sustainable diets for all – and with adequate adoption can partly solve problems of climate change better than modern, industrial, and capital-intensive systems (Gliessman 2022).

Despite all the positive attributes of agroecology, it has been criticized for the accuracy of its core objectives such as sustainable agriculture, improved interactions between animals and plants, and humans and the environment. It was specifically criticised for advocating that the world should be fed through alternative farming systems (organic), which rarely have higher yields and productivity compared to the conventional systems (Kassie et al. 2009). Batary et al (2011) specifically criticised agroecology that its scientific principles are subject to the law of uncertainty, which can yield results different from the expected ones.

This theory is adequately applied to the subject, especially in the area of de-emphasising over-reliance on foreign experts or scientists by African states. Due to emerging and traditional issues, concerns such as COVID-19, climate change, conflicts, poverty, and hunger have remained vulnerable to exploitations, impositions, and the hegemonic power of developed countries. Against the doctrine of agroecology theory, the hoodia plants of the San tribe in Southern Africa were processed and announced without prior informed consent and observance of the basic principle of geographical indications as attributes of Convention on Biological Diversity – an integral part of the intellectual property rights as recognised by international law (Amusan 2017). Even though there was the combination of science (processing of hoodia plants) with traditional knowledge (the discovery of hoodia as a medicinal plant), evidence, as pointed out by Amusan (2017) shows that multinational corporations never considered the aspirations and ethical values of the Khois and Sans tribes.

For Amusan (2017) and Michieka (2022), just like agroecology theory, any collaboration or support from developed nations, such as China and America, with an act to combine science with local traditional knowledge in an unfair manner or in such a way to limit the autonomy of the receiving states or against their aspirations cannot boost sustainable food production in Africa. The current trend of land and water grabs with little or no tangible compensation, under the guise of producing more food that will meet the hunger and malnutrition aspirations of Africa by multinational corporations from China and America is enough evidence to show that most of the purported support is only a conduit pipe used in milking Africa’s resources (Allan, Keulertz, Sojamo & Warner 2013). Amusan (2018) also shared a similar view about most support coming from developed countries, it was revealed that the majority of support offered to host countries are done to repatriate huge profits and create jobs through outsourcing.

On the issues of ethical values and aspirations of host countries as opined by agroecologists, Mbamalu (2018) found that most Chinese firms and investments in Africa are guilty of labour abuse and lack of respect for certain societal ethical values. The presence of China especially in areas of food production is detrimental to Africa’s food security quest. This is against the much-hyped boosting of Africa’s food security at the Eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation held in Dakar, Senegal in November 2021. At the theoretical level, the Conference aimed to ensure cooperation in agriculture through Vision 2035 (Xiaohui 2022). America too, through Bretton Woods institutions (the IMF and World Bank) contributes in no small way to Africa’s impoverishment (Asad 2004; Bernstein 2007; Toussaint 2008). America, through these two institutions, has worked tirelessly to integrate Africa to operate in the subordinate position of suppliers of raw materials and open markets for the US-dominated global capitalist system (Adas 2006; Asad 2004). America through its various international institutions and food policies has used the Western media to sell the idea of GMOs to Africa (Howard 2016; Walters 2011). America’s imposition and intensification of policies and systems began with the enforcement of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the early 1980s in third world countries. Ostensibly aimed at stabilizing poor countries. In the real sense, it was a means to maintain hegemonic power over these poorer countries. It aimed at reducing the volume of money in circulation, promoting liberalization of trade, prohibiting controls on foreign exchange, flexible labour markets (in other words, a lowering of labour standards) and encouraging more privatization among others. All of these have implications across sectors (such as cut-backs on education, health, elimination of subsidies and marketing boards for agricultural products).

Against America’s theoretical intensification of export expansion and foreign investment and support in Africa, it has not increased Africa’s growth, or reduced debt and poverty. Tax holidays and repatriation tax allowances also reduced the contribution of foreign investment to Africa’s development. This is added to the fact that most African exports are raw materials sold at cheap prices. Contrary to the principle of agroecology that questions the imposition of western ideas and policies on African states, the two decades of SAP’s further impoverished the continent across sectors, including the agricultural sector. In addition, several states in Africa are experiencing large scale US-led charitable activities in collaboration with USAID humanitarian assistance in the area of food security. It is worth noting that this has not alleviated hunger and poverty in the continent (Malkan, 2021).

The imposition of scientific and foreign knowledge to discredit indigenous knowledge is one other notable means of how China-America rivalry in Africa’s food security sector has further impoverished Africa’s quest for food sovereignty. Like agroecology, a blend of both knowledge (scientific and traditional), autonomy and adaptive capacity of the receiving states are critical in achieving food security in Africa. However, evidence from Asad (2014), Amusan (2014), Amusan (2018), and McGown (2006) show that support from China and America is largely offered to suffocate indigenous knowledge systems through patenting policies despite globally acknowledged geographical indications, and access, benefit and sharing together with international trade of unequal exchange. Amusan (2018) specifically attributes the cause of this to the display of hegemonic dominance in the form of diplomatic and negotiation powers, influence, economic preponderance and socio-cultural ability, which overrides the bargaining prowess and the autonomy of African countries during negotiations for partnerships and collaborations (Soobramanien 2011). The gradual replacement of organic food with GMOs as well as the patenting of Africa’s plants and animals confirm the above consequences of the China-America rivalry in search of food security in Africa (Bond 2006).

From the perspective of agroecology theory, sustainable food must reflect the aspirations of societies in need of help and partnership. Aspirations represent involvement, consultations, and active participation of local producers or communities in the decision-making process of food production systems. In essence, local farmers in Africa should actively participate in the affairs that concern their food production. However, the reverse has been the case since China and America’s scramble for superiority in search of food security in Africa began. Both countries, through their agents such as World Trade Organizations WTO, Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), MNCs or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), and Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs, technology) and Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs, trade-in service) have taken vital agricultural decisions. Their roles in the marketing of agricultural products, price fixing of farm produce, seedlings, fertilizers, pest control, cultivation, harvesting, and storing systems without any contributions from local farmers, who largely contribute to food quantity and quality in Africa calls for concern (Amusan, 2018). In the name of support to Africa, these two countries, through the WTO have taken decisions that affect the lives and productivity of African farmers without any role played by these farmers. For example, most of the support in the agricultural sector by these global economic giants has always favoured men over women farmers. In other words, their supports tend to have intensified gender inequality, which had, for long been skewed against women in Africa’s agricultural sector. Bayne and Woolcock (2011) and Nwoke (2013) conclude that decisions by these donors on critical agricultural issues without the involvement of local producers are the leading cause of the alienation of women in the agricultural sector.

Overbearing political powers of multinational corporations have been used to make and implement decisions that forced citizens of host states to accept the production and consumption systems of the global economic giants. They have effectively devised and deployed the CSR strategy to trick and sometimes force local citizens in host countries to openly accept their consumption systems. The continual use of the western media, through highly information-packed advertisements to persuade Africans of the alternative to organic food systems, is a strategy meant to give Africa directives that indirectly limits African’s autonomy to decide on what, where, and how to eat. In other words, with support from China and America, under the guise of promoting Africa’s food security aspiration, the continent has unknowingly relinquished its power to determine what to produce, where to produce, and how to produce to these global economic giants.

The review and application of agroecology on China-America’s rivalry in search of food security in Africa show that none of the positive attributes of this theory were followed by either country in their partnerships with Africa. Both countries offered support chiefly to foster their national interests. Even in some instances where they have rightly transferred technology to address the impacts of climate change on Africa, results of extant studies from Asad (2004), and Amusan (2018) revealed that such a gesture is largely based on a show of their control and influence on beneficiaries. This is in addition to the fact that the majority of these know-how transfers are inferior and inappropriate for use as local farmers rarely have access to and lack adequate knowledge of the use of state-of-the-art technologies when they are eventually made available (Amusan 2018). Principles such as autonomy of African states at the negotiation stage, respect for ethical values and aspirations of the African states contest against the intensification and standardization of food production and consumption systems. They have rather resorted to the use of CSR to deceptively dislodge Africans of their land and water in the guise of food-for-all through controversial large-scale farming (Howard 2016; Pearce 2012; Walters 2011). Similarly, Africa’s food production and consumption systems have been unduly altered with the global intensification of the adoption of GMOs. Today, despite the influence of China and America, Africa remains largely food insecure.

US-China Rivalry in Search of Africa’s Food Security

The strategic rivalry between America and China has intensified over the years. It has become acute in Africa as both countries scramble for control of key sectors, especially agriculture. The two states have noticed that their rivalry could make them vulnerable, so they have sought ways to expand their economic, geopolitical security, technology, and food security interests while seeking new sources of competitiveness (Ferchen 2021). While the rationale for their rivalry has been extensively analysed, the implications of this for sustainable development in critical sectors in Africa are equally important. It is imperative to state that the need for global primacy is the major goal of the US-China rivalry (Ferchen, 2022). Although both pledged their support for Africa in the agricultural sector, their goals differ. While in reality, the need to feed China’s billion+ population is a huge determinant of Beijing’s support in Africa’s agricultural sector; America’s interests are driven by business and profit-making in the services sector of agribusiness, especially in areas of food, feed and biofuels (Howard 2016). In the pursuit of their interests, they tend to clash over dominance and influence in critical sectors such as infrastructure, food, technology, and health governance. As much as one may hold this position, globalization through the WTO has made a global village where many of America’s corporations are active in China due to cheap labour and market concerns. At the same time, the recent acceptance of GMOs in China points to the cooperation and complementary activities of the two states when it comes to looting African resources (Burgis 2015; Pearce 2012).

While China is more interested in development-focused economic diplomacy with Africa through what Will Hutton (2006) terms as “soft infrastructure of capitalism”, which has bolstered trade, financial relations, and investment, America is more interested in smart businesses, which are heavily based on the capitalist system. US-China supports in Africa are laden with competition that sometimes overlaps with the strategic aim of their country; undercutting, and complicating their government’s decision. It is clear that this rivalry draws on both recent elements and on Cold War legacies ranging from economic, technology, military, and geopolitical competition, as well to struggle for prestige and status (Ferchen 2021). From a Cold War perspective, China has underpinned its contemporary support for Africa in Third World friendship. The US, on the other hand, argues that its contemporary rivalry with China is connected to ideological differences and has warned African countries to be wary of communist-prone support that is heavily state-dominated (Goh and Liu, 2021).

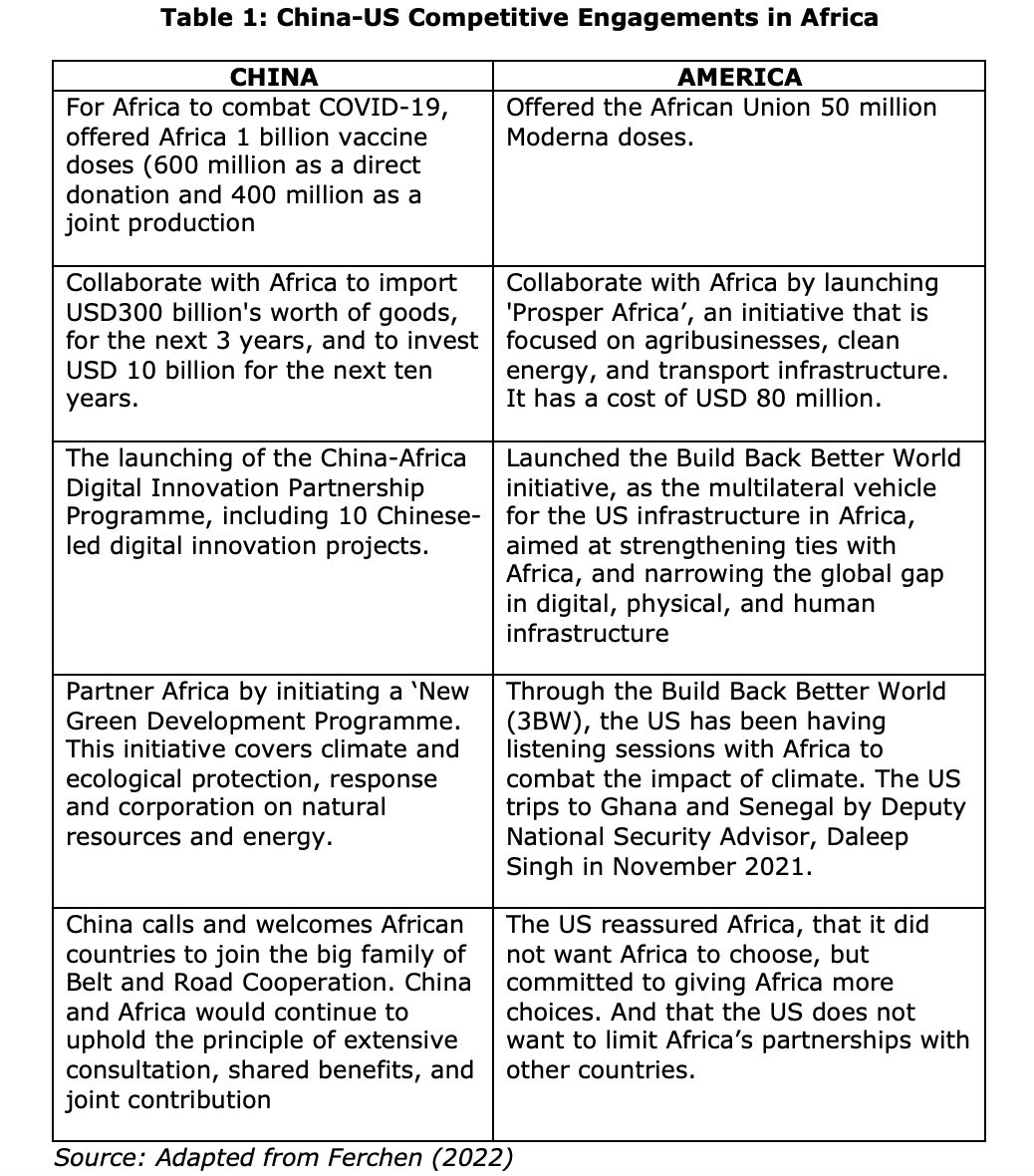

In Africa, China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI), which largely supports African governments in infrastructure and construction to ease the movement of food from the farm to the market, has received several criticisms and responses from the US (Shambaugh 2020). One criticism focuses on the use of inferior technologies and the large numbers of Chinese as workers on these roads which confirms the findings by Amusan (2018) that obsolete and inferior technologies are frequently supplied to Africa. Evidence also showed that China and America compete in technology, as both of them scramble for a market for their technologies and government support (Ferchen 2022; Sun & Olin-Ammentorp 2014). China’s development-themed economic diplomacy in Africa, which covers critical sectors like trade, agriculture, food, and financial aid among others, is laced with cooperation rather than the paternalistic initiative of the US (Kurlantzick, 2008). The US sees this as a confrontation and criticised China for impoverishing Africa through unsustainable loans, the unsustainability of commodity-dependent trade ties, and harmful environmental impacts. The US, in the heat of the rivalry, has described China’s loan as “predatory” and that receiving support from an authoritarian state like China could breed corruption, dependency, and political instability, rather than sovereignty, progress, and prosperity (Xuetong, 2019). Against China’s BRI, the US initiated ‘The Prosper Africa trade and investment policy and the Infrastructure Cooperation Scheme’; and ‘Africa Growth and Opportunity Act’ (AGOA) (Pompeo, 2020). Part of the reason why America established the Africa Command was to compete with China’s military and private security firms, established to safeguard China’s commercial and citizen presence in Africa; and to control the fossil fuel in the continent (Amusan 2016). Other critical areas of their competition are explained in table 1.

Conclusion

China-America rivalry in search of food security has made both countries committed to Africa in different ways ranging from finance, technology, ecology, digital communication, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and protection. This rivalry has raised questions as their actions deviate significantly from the core principles of agroecology, which stipulates that sustainable food for the future of any state is better achieved through a combination of science and technology with local indigenous knowledge and adequate respect for ethical values, societal aspirations, autonomy and due consultation with local producers. Results of extant studies and analysis in this article show that China and America are more interested in establishing their influence, status, and prestige across critical sectors (such as agriculture) in Africa than boosting food security and rescuing Africa from problems of hunger and malnutrition. This is evident in their intensification of GMOs, patents, transfer of inappropriate technologies, disregard for ethical values in terms of the right of ownership of food, land and water grabs under the pretence of cultivation of food for Africans, disrespect of some African countries’ autonomy, and the alienation of local producers from the decision-making process, among others. Can Africa achieve sustainable food for its future generations if China and America continue to display such a model of partnership? This will be difficult unless both countries rethink their approaches and embrace cooperation using platforms such as the WTO and CBD.

References

Action Against Hunger. (2022). World Hunger: Key Facts and Statistics. https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/world-hunger-facts-statistics.

Adas, M. (2006). Dominance by design: technology imperatives and America’s civilizing mission. Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Havard University Press.

Agunyai, S.C. (2023). Global Partnerships, Land Grabbing, and Food Insecurity in Africa: Insights from the African Parliament. African Renaissance, 20(4), 23-31.

Agunyai, S. C., and Lere Amusan (2023). “Implications of Land Grabbing and Resource Curse for Sustainable Development Goal 2 in Africa: Can Globalization Be Blamed?” Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10845.MDPI https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410845

Allan, T., Keulertz, M., Sojamo, S. and Warner, J. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of Land and Water Grabs in Africa: Foreign Direct Investment and Food and Water Security. New York: Routledge.

Altieri M. A. (1995) Agroecology: the science of sustainable agriculture. Westview Press, Boulder.

Amusan, L. (2019). Mercy Killing and Thanksgiving: Food Security with Tears in Africa. Being a Paper Presented at Faculty Distinguished Lecture Series 1 Held on Friday, May 17, 2019. Faculty of Social Sciences, Federal University, Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.21142.78407

Amusan, L. (2018), “Multinational Corporations’ (MNCs) Engagement in Africa Journal of African Foreign Affairs 5(1) 41- 62

Amusan, L. (2017). “Politics of Biopiracy: An Adventure into Hoodia/Xhoba Patenting in

Southern Africa”, African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine 14(1):103-109.

Amusan, L. (2016). “Marsupial Babies in the Midst of Plenty: America’s Dominance by Design in the Gulf of Guinea”, Journal of Social Sciences, 48(3): 203-212.

Amusan, L. (2015). “Imposed Socially Responsible Pricing on AIDS/HIV in Developing Areas: South Africa and Multinational Pharmaceutical Companies,”. Indian Quarterly, 71(1): 67-79.

Amusan, L. (2014), “The Plight of African Resources Patenting through the Lenses of the World Trade Organisation: An Assessment of South Africa’s Rooibos Tea’s Labyrinth Journey” African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 11(5): 41- 47.

Amusan, L. (2010), “Climate-smart and security challenges in the Oil and Gas Industry in Africa: an Assessment of the Marginalized Niger Deltans” in Ojakorotu, V and Isike, C.A. (Eds.) Oil Politics in Nigeria: Niger Delta, Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrücken. pp: 41-59.

Amusan, L. and Olutola, O. (2016). “Paris Agreement (PA) on Climate Change and South Africa’s Coal-Energy Complex: Issues at Stake” Africa Review Vol.9 No. 1 pp: 43-57

Asad, I (2004). Impoverishing a Continent: The World Bank and the IMF in Africa. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Economic development projects, pp.1-27, https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National_Office_Pubs/africa.pdf. Accessed 14/04/2022.

AU (African Union). 2022. African Countries adopt Common African Position to Integrate Gender Equality in Climate Action Agenda. 03 March 2022.Press Releases. https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20220303/african-countries-adopt-common-african-position-integrate-gender-equality. Accessed 15/4/2022.

Bayne, N. and Woolcock, S. (Eds.) (2011), The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiation in International Economic Relations, London: Ashgate,

Batáry P, Báldi A, Kleijn D, Tscharntke T (2011). Landscape-moderated biodiversity effects of agri-environmental management: a meta-analysis. Proc R Soc B 278(1713):1894–1902. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1923, 22.

Bernstein, H. (2007). Structural adjustment and African agriculture: a retrospect. In Moore, D. (ed). The World Bank: development, poverty, and hegemony. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, p. 343-368.

Bond, P. (2006). Looting Africa: The Economics of Exploitation. London and New York: Zed Books.

Burgis, T. (2015). The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth. New York: PublicAffairs.

Callon M, Lascoumes P, Barthe Y (2001) Agir dans un monde incertain. Essai sur la démocratie technique. Le Seuil (La couleur des idées), Paris

Carmody, P. (2011). The New Scramble for Africa. London: Polity Press.

Economy, E. (2018). The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Economy, E. (2007). “The Great Leap Backward?: The Costs of China’s Environmental Crisis,” Foreign Affairs. 86(5): 38-59.

Ferchen, M. (10 February 2021), “Towards ‘extreme competition’: Mapping the contours of US-China relations under the Biden administration,” https://merics.org/en/report/towards-extreme-competitionmapping-contours-us-china-relations-under-biden-administration. Accessed 14/04/2022.

Ferchen, M. (4 March 2022), “Growing US-China rivalry in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia,”: Implications for the EU, Metrics China Monitor, https://merics.org/en/report/growing-us-china-rivalry-africa-latin-america-and-southeast-asia-implications-eu Accessed 14/04/2022.

Gliessman, S. R. (2022) Agroecology in a changing climate, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 46:4, 489-490, DOI: 10.1080/21683565.2022.2049968.

Gliesmann. S. R. (2015). Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Goh, E and Liu, N (2021), “Chinese Investment in Southeast Asia, 2005-2019: Patterns and Significance,” Australian National University Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, https://www.newmandala.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GohLiu_-SEARBO2_Chinese-Investment-in-SoutheastAsia-2005-20192.pdf. Accessed 14/04/2022.

Howard, P. H. (2016). Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Hutton, W. (2006). The Writing on the Wall: China and the West in the 21st Century. London: Little, Brown Book Group.

Kaplinsky, R and Messner, D (2008). Introduction: the impact of Asian Drivers on the developing world. World Development, 36(2), pp. 197–209

Kassie M, Zikhali P, Pender J, Köhlin G (2009) Sustainable agricultural practices and agricultural productivity in Ethiopia: does agroecology matter? Environment for Development, April 2009, DP-09-12, 43 p

Kurlantzick, J (2008), Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World, Yale University Press

Li, W., Grimm, S., & Esterhuyse, H. (2013). China-Africa cooperation: Joint engagement in adaptation to climate change. In O. C. Ruppel, C. Roschmann, & K. Ruppel-Schlichting (Eds.), Climate change: international law and global governance Nomos Publishers. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845242774_529.

Lymbery, P. and Oakeshott, I. (2014). Farmageddon: the true cost of cheap meat. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Malkan, S. (2021). African Groups Want Gates Foundation, USAID to Shift Agricultural Funding as Hunger Crisis Worsens. 8 September. https://usrtk.org/bill-gates-food-tracker/agra-donors/. Accessed 16 April 2022.

Mbamalu, S. (2028). The plight of African Workers under Chinese Employers. African Liberty. https://www.africanliberty.org/2018/09/27/plight-of-african-workers-under-chinese-employers/

McGown, J. (2006), Out of Africa: Mysteries of Access and Benefit Sharing, Washington & Richmond: Edmond Institute & African Centre for Biosafety.

Michieka, R. (2022). Why Africa Needs Access to Both Traditional Agricultural Tools and Cutting-Edge Biotechnology Innovations. 1 April. https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2022/04/01/why-africa-needs-access-to-both-traditional-agricultural-tools-and-cutting-edge-biotechnology-innovations/?utm_source=jeeng. Accessed 16 April 2022.

Nyasimi M, Radeny M, Kinyangi J. (2013). Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Initiatives for Agriculture in East Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 60. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org

Nwoke, C. N. (2013), “Nigeria’s National Interest in a Globalized World: Completing the Independence Project”Nigerian Journal of International Studies, 38(1&2): 89-91.

Olander, E. (2021). Why Food Security & Agriculture Issues Need to Be Atop the China-Africa Agenda. The China-Africa Project https://chinaafricaproject.com/podcasts/why-food-security-agriculture-issues-need-to-be-atop-the-china-africa-agenda/. Accessed 14/04/2022

Onimode, B. (2004), “Mobilisation for the Implementation of Alternative Development Paradigms in 21st Century Africa” in Onimode, B. (Ed.) African Development and Governance Strategies in the 21st Century: Looking Back to Move Forward. London & New York Zed Books, pp. 20-29.

Paarlberg, R. (2013). Food Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York and London: Oxford University Press.

Patey, L. and Chun, Z. (2021). How US-China Team Effort in Africa Could Lower Tensions and Benefit All. 3 December. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3158026/how-us-china-team-effort-africa-could-lower-tensions-and-benefit?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article&campaign=3158026. Accessed 14 April 2022.

Pearce, F. (2012). The Land Grabbers: The New Fight Over Who Owns the Earth. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pfadenhauer, M and Knobllauch, H. (2019). Social Constructivism as Paradigm?: The Legacy of the Social Construction of Reality. London and New York: Routledge.

Pompeo, M. (19 February 2020), “Liberating Africa’s Entrepreneurs,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, https://2017-2021.state.gov/liberating-africas-entrepreneurs/index.html. Accessed 14/04/2022.

Ravenhill, J. (2017). Global Political Economy. London and New York: Oxford University Press.

Shambaugh, D. (2020), Where Great Powers Meet: America and China in Southeast Asia, Oxford University Press.

Soobramanien, T. (2011). “Economic Diplomacy for Small and Low-Income Countries.” In Bayne, N. and Woolcock, S. (Eds.), The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiation in International Economic Relations. Surrey, England & Burlington, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company, pp. 187-204.

Sun, Y and Olin-Ammentorp, J. (2014). “The US and China in Africa: Competition or Cooperation?” 28 April. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/04/28/the-us-and-china-in-africa-competition-or-cooperation/. Accessed 18 April 2022.

Sutter, R. G. (2016). Chinese Foreign Relations: Power and Policy since the Cold War. New York and London: Rowman & Littlefield.

The Conversation. (2020). Africa Countries Need to Seize Opportunities Created by US-China Tensions. 15 June. https://theconversation.com/african-countries-need-to-seize-opportunities-created-by-us-china-tensions-140448. Accessed 15 April 2022.

Thomas, C., Lamy, S. L., and Masker, J. (2019). “Poverty, Development and Hunger,” in Lamy, S. L., Masker, J. S., Baylis, J., Smith, S. and Owens, P. (Eds.) Introduction to Global Politics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 334-342.

Toussaint, E. (2008). The World Bank: a critical primer. London: Pluto Press.

USAID (2021). Africa Trade and Investment Program Fact Sheet, https://www.usaid.gov/documents/africa-trade-and-investment-program-fact-sheet-0. Accessed 14/04/2022.

Walters, R. (2011). Eco Crime and Genetically Modified Food.New York & London: Routledge.

Webb, P. and Thorne-Lyman, A. (2007). “Entitlement Failure from a Food Quality Perspective: The Life and Death Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Humanitarian Crisis,” in Guha-Khasnobis, B., Acharya, S. S. and Davis, B. (Eds.) Food Insecurity, Vulnerability and Human Rights Failure. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 243-265.

WFP (World Food Programme). 2021. Hunger pandemic: Food security report confirms WFP’s worst fears. 12 July. https://www.wfp.org/stories/hunger-pandemic-food-security-report-confirms-wfps-worst-fears.

Xiaohui, Y. (2022). Boosting Africa’s Food Security. China Daily. 11 February. https://www.chinadailyhk.com/article/259283.

Xuetong, Y. (2019). “The Age of Uneasy Peace: Chinese Power in a Divided World,” Foreign Affairs. 98(1): 40-46

Further Reading on E-International Relations

[ad_2]